Did Lincoln Free the Slaves?

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to “be received into the armed service of the United States.”

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the final version of the Emancipation Proclamation.

I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do … order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion, against the United States, the following, to wit:

Lincoln then listed the ten states still in rebellion, excluding parts of states under Union control, and continued:

I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free… [S]uch persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States… And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

The proclamation provided that the executive branch, including the Army and Navy, “will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.” Even though it excluded areas not in rebellion, it still applied to more than three and a half million of the four million enslaved people in the country. Around 25,000 to 75,000 were immediately emancipated in those regions of the Confederacy where the US Army was already in place. It could not be enforced in the areas still in rebellion, but, as the Union army took control of Confederate regions, the Proclamation provided the legal framework for the liberation of more than three and a half million enslaved people in those regions by the end of the war. The Emancipation Proclamation outraged white Southerners and their sympathizers, who saw it as the beginning of a race war. It energized abolitionists and undermined those Europeans who wanted to intervene to help the Confederacy. The Proclamation lifted the spirits of African Americans, both free and enslaved. The proclamation encouraged many to escape from their masters and flee toward Union lines to obtain their freedom and to join the Union Army. [1]

The Emancipation Proclamation became a historic document because it “would redefine the Civil War, turning it [for the North] from a struggle [solely] to preserve the Union to one [also] focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict.”[2]

Juneteenth

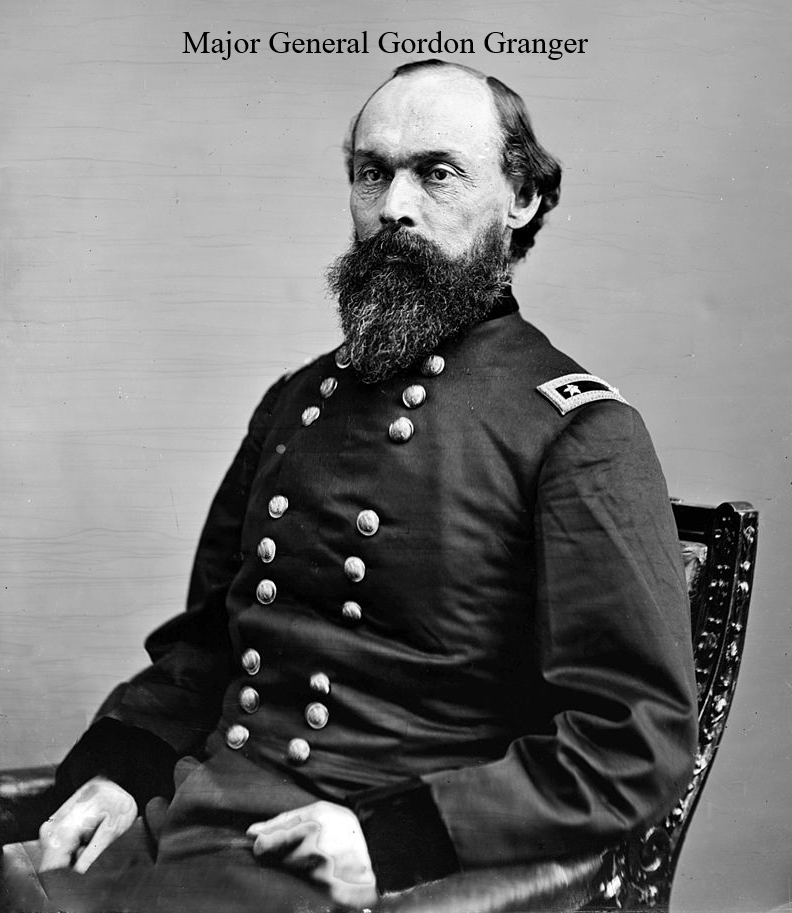

Juneteenth (officially Juneteenth National Independence Day) is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. Deriving its name from combining June and nineteenth, it is celebrated on the anniversary of the order, issued by Major General Gordon Granger on June 19, 1865, proclaiming freedom for slaves in Texas. The celebration began in Galveston, Texas. Juneteenth has since been observed annually in various parts of the United States, often broadly celebrating African-American culture. The day was first recognized as a federal holiday in 2021 when President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act into law after the efforts of Lula Briggs Galloway, Opal Lee, and others.

Despite the surrender of Confederate General-in-Chief Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, the Western Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi did not surrender until June 2. On the morning of June 19, 1865, Union Major General Gordon Granger arrived on the island of Galveston, Texas to take command of the more than 2,000 federal troops recently landed in the Department of Texas to enforce the emancipation of its slaves and oversee Reconstruction, nullifying all laws passed within Texas during the war by Confederate lawmakers. The order informed all Texans that, in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves were free:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Urban legend places the historic reading of General Order No. 3 at Ashton Villa; however, no existing historical evidence supports such claims. Although widely believed, it is unlikely that Granger or his troops proclaimed the Ordinance by reading it aloud: it is more likely that copies of the Ordinance were posted in public places, including the Negro Church on Broadway since renamed Reedy Chapel A.M.E. Church. On June 21, 2014, the Galveston Historical Foundation and Texas Historical Commission erected a Juneteenth plaque where the Osterman Building once stood signifying the location of Major General Granger’s Union Headquarters and subsequent issuance of his general orders.

Although this event has come to be celebrated as the end of slavery, emancipation for the remaining enslaved in two Union border states (Delaware and Kentucky), would not come until several months later, on December 18, 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified. The freedom of former slaves in Texas was given state law status in a series of Texas Supreme Court decisions between 1868 and 1874.[3]

[1] “Emancipation Proclamation,” Wikipedia, Emancipation Proclamation – Wikipedia, retrieved June 17, 2023.

[2] “Emancipation Proclamation – Definition, Dates & Summary,” History, Emancipation Proclamation – Definition, Dates & Summary – HISTORY (archive.org) retrieved June 17, 2023.

[3] “Juneteenth,” Wikipedia, Juneteenth – Wikipedia, retrieved June 17, 2023.