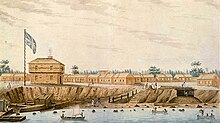

Fort York is an early 19th-century military fortification in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It was used to garrison British and Canadian soldiers and defend the Toronto Harbor entrance. The fort contains stone-lined earthwork walls and eight historical buildings, including two blockhouses. It is part of Fort York National Historic Site, a 41-acre site that includes the fort, Garrison Common, military cemeteries, and a visitor center.

The fort was developed from a garrison established by John Graves Simcoe in 1793. British-American tensions resulted in additional enhancements to the fort, and it was designated as an official British Army post in 1798. The original fort was destroyed by American forces following the Battle of York in April 1813. Work to rebuild the fort began later in 1813 over the remains of the old fort and was completed in 1815. The rebuilt fort served as a military hospital for the remainder of the War of 1812, It also defended against an American naval vessel in August 1814.

Fort York remained in use with the British Army and the Canadian militia despite the opening of New Fort York to the west in the 1840s. In 1870, the property was formally transferred to the Canadian militia. The municipal government assumed ownership of the fort in 1909, although the Canadian military continued to make sporadic use of it until the end of the Second World War.

The fort and the surrounding area were designated as a National Historic Site of Canada in 1923. The fort was restored to its early-19th-century configuration in 1934 and reopened as a museum on the War of 1812 and military life in 19th-century Canada.

History

The British first examined Toronto as a potential settlement and military site during the 1780s. However, a permanent military presence was not established in Toronto until 1793, when Anglo-American relations had deteriorated. In the early 1790s, John Graves Simcoe, the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, began to consider building a fort in Toronto as a part of a larger effort to reposition isolated British garrisons in the U.S. Northwest Territory and near the Canada–United States border to more centralized positions, and to vacate British forces from U.S. territory in an attempt to reduce tensions with the Americans. Simcoe’s decision to base a fort in Toronto was also influenced by his assessment that American forces could overrun its positions in the frontier, including its naval base in Kingston.

Simcoe selected Toronto (renamed York from 1793 to 1834) as the location of a new military garrison due to its proximity to the border and because its natural harbor only had one access point from water, making it easy to defend. Once established, Simcoe envisioned the harbor as a base where British control over Lake Ontario could be exerted and where they could repel a potential American attack from the west into eastern Upper Canada.

He also envisioned the fort serving as the center of a transportation network where British forces could be dispatched throughout the colony. Simcoe planned for the fort to be connected to a network of subsidiary fortifications along a series of east-west roads acting as an alternate transportation route to the Great Lakes, and the north-south portage route that leads to the Georgian Bay. The latter route was vital for maintaining communication with British outposts in lakes Huron, Michigan, and Superior, in the event the routes through Lake Erie and the Detroit River become cut off by the American forces however, many of the planned subsidiary forts were never built, with Simcoe unable to procure the funds needed to build them.

Original fort (1793–1813)

The first permanent British garrison was established in Toronto on 20 July 1793, when 100 soldiers from the Queen’s Rangers landed around Garrison Creek; and erected 30 cabins built from green wood on the site of the fort for wintering quarters; configured in a triangular shape similar to the present fort’s shape. Simcoe planned for Fort York to be a part of a defence complex built around the settlement’s harbour, with the fort situated north of another fortification planned at Gibraltar Point. However, his proposal to further fortify the settlement was rejected by the governor general of the Canadas, Lord Dorchester, who took the position that the money should instead be spent on improving the defences at the naval base in Kingston.

Simcoe continued the construction of Fort York despite the governor general’s objections. He relied on funds from the provincial treasury instead of military funds because the fort was not an official army post. By November 1793, Fort York consisted of two log barracks, a stockade, and a sawmill. Over the next year, the Queen’s Rangers built a guard house and two blockhouses near Gibraltar Point. The fort defended the harbor’s entrance, the most likely landward approach the Americans would take toward the settlement. British planners believed American forces would land west of the harbor and advance towards the settlement with the support of its naval vessels. Simcoe continued to develop York’s fortifications until the end of 1794, when he realized that York needed more armaments.

When most of the colony’s administration was relocated to York in 1796, the fort was manned by a 147-man garrison. However, Fort York’s defensive capabilities remained limited. Two other blockhouses were erected around the settlement, including one at Fort York. The blockhouse at Fort York also featured a cupola used to guide ships into the harbor.

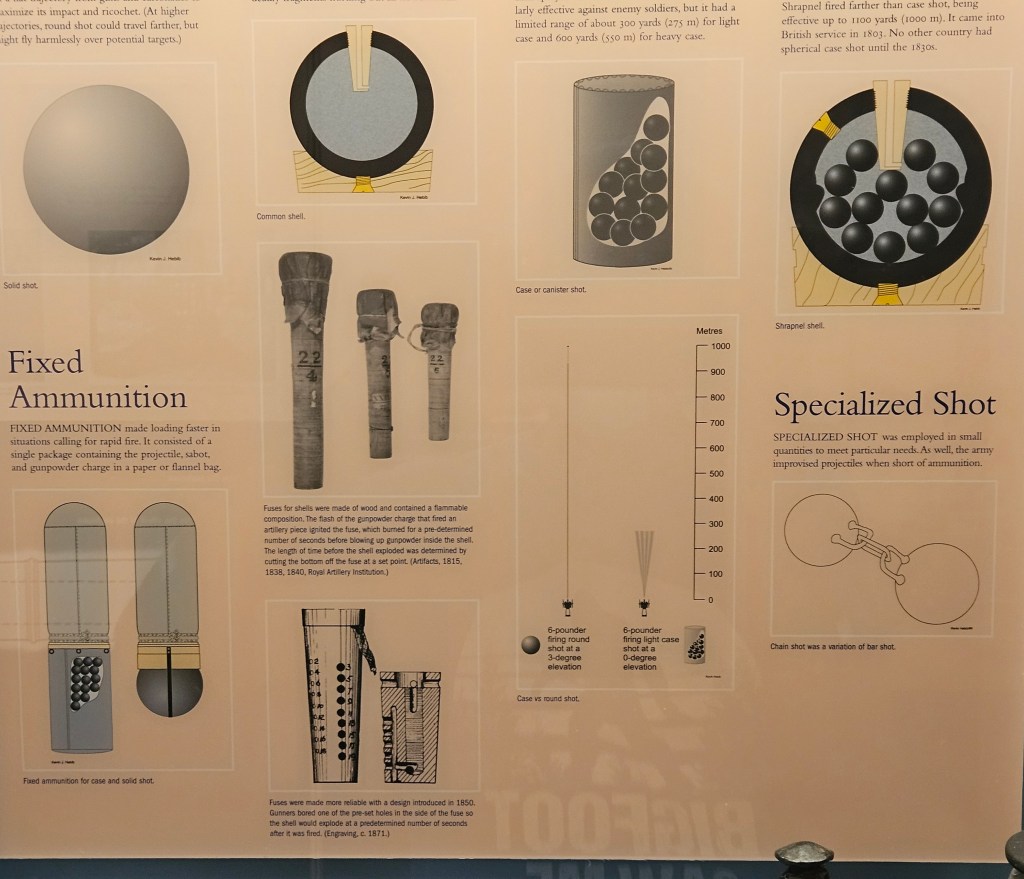

In late 1798, Fort York became an official British Army post, allowing it access to funds reserved for military use. A stockade was built around the fort. Many of its original structures were also replaced with new buildings, including barracks, carriage and engine shed, the colonial government house, guardhouse, gunpowder magazine, and storehouses. As British-American tensions increased again at the beginning of the 19th century, Major-General Isaac Brock ordered the construction of three artillery batteries, and a wall and dry moat on the western boundary of the fort. The batteries were equipped with furnaces, allowing the batteries to fire heated shot, with further 12-pounder guns placed on mobile carriages used to respond to threats outside the fixed ranges of the batteries.

Simcoe’s original proposal of using York as a naval base was also reconsidered during the early 19th century, with plans to expand the fort near Government House to accommodate a naval base. However, as the majority of the naval assets in Upper Canada were based in Kingston, the governor general of the Canadas, George Prévost, planned to make the move to York in phases.

When news of the American declaration of war arrived at York, the regulars and military cavalry squad of the fort left for the Niagara peninsula, eventually participating in the Battle of Queenston Heights. While its garrison was deployed in the Niagara, Fort York was manned by the Canadian militia.

Battle of York

The town of York was attacked by American forces in April 1813. The attack formed the first part of Henry Dearborn’s plan to take the Canadas by first attacking York, then the Niagara peninsula, Kingston, and finally Montreal. Fort York formed a part of the settlement’s defences, which included batteries and blockhouses around the town and Gibraltar Point. After reports of approaching American ships reached the settlement, most professional troops in the area, First Nations-allied warriors, and some members of the local militia assembled at the fort.The regulars and militias stationed at the town’s blockhouse were later ordered to reassemble at Fort York once it was made apparent that no landings would occur east of the settlement.

Most of the fighting occurred during the American landing, approximately 1.2 miles west of the fort. Canadian forces could not prevent the landings or repel the force at the western battery. The British-First Nations force retreated to the fort. American forces advanced east towards the fort, assembled outside its walls, and exchanged artillery fire with the fort. The American naval squadron also bombarded the fort. Recognizing that the battle was lost, The British commanding officer, Roger Hale Sheaffe, recognized that the battle was lost, ordered a silent withdrawal from the fort, and rigged the fort’s gunpowder magazine to explode to prevent its capture. The two sides continued to exchange artillery fire until Sheaffe’s withdrawal from the fort was complete. Because the British flag was left on the flagpole of the fort, the Americans assembling outside its walls assumed the fort remained occupied.

The gunpowder magazine contained 74 tons of iron shells and 300 barrels of gunpowder. When the magazine exploded, a massive amount of debris was launched into the air and dropped onto the American forces outside the fort. The explosion caused over 250 American casualties, including Brigadier General Zebulon Pike. Anticipating a counterattack after the blast, American forces regrouped outside the wall and did not advance onto the abandoned fort until after British forces left York.

The fort was occupied by the American forces after the town’s surrender. During the brief occupation, members of the militia were detained in the fort for two days before being released on “parole.” The British dead were buried within the fort in shallow graves, although they were later reburied outside the fort after the Americans left. Before they departed from York on May 1, 1813, the American forces burned several buildings, including most of the structures in the fort, except its barracks.

Rebuilt Fort (1813-1932)

Plans to rebuild the settlement’s defences, including the fort, and the surrounding blockhouses were undertaken in the second half of 1813 to defend a four-vessel squadron the Royal Navy planned to station at York’s harbour. Several structures were completed at the fort by November 1813, including the Government House Battery and the Circular Battery, each equipped with two 8 inch mortars; with another two blockhouses nearing completion. The blockhouses were also designed to act as barracks for the town’s garrison, in order to allow for the immediate garrisoning of troops in the settlement.In the following years, the forest around the fort was cleared to deprive Americans of cover in the event of another attack; and the defensive earthworks, barracks, and gunpowder magazine were rebuilt. The fort was not completed until around 1815; due to small numbers of artificer available at York, and a warm 1813–14 winter preventing the use of sleighs to transport supplies during that season.

The fort operated as a hospital centre from the latter half of 1813 to the end of the war, with the naval squadron stationed at York assisting in transporting wounded soldiers from the Niagara front to the town. On August 6, 1814, an American naval squadron arrived near York’s harbor under the suspicion that British vessels were stationed there. The squadron dispatched the USS Lady of the Lake to sail into the harbour under a white flag in a ploy to evaluate the town’s defences. However, the militia stationed in the fort shot at the vessel, resulting in the two sides exchanging fire before the Lady of the Lake withdrew back to its squadron outside the harbour. The American squadron did not attempt another attack on the fort, although remained outside York’s harbour for three days before sailing away.

Post War of 1812

Work on the fort stopped at the end of the war. By 1816, the rebuilt fort included eighteen buildings capable of holding a garrison of 650 soldiers. An additional 350 soldiers could also be garrisoned in military facilities adjacent to the fort. After the war, the fort continued to be a point of focus for military planners in the region, with York envisioned as an area that could provide cover for a retreat to Kingston and Lower Canada, or as a rallying point for British forces to defend the Niagara peninsula. The British also continued to use the fort to protect the north-south portage route to the upper Great Lakes.

In the decades after the War of 1812, several buildings within the fort were torn down and replaced. However, the fort’s conditions were primarily shaped by British foreign relations, as it suffered from poor maintenance during times of peace and underwent repairs and reinforcing during perceived signs of hostilities. By the early 1830s, it had become apparent that new fortifications needed to be built to replace the decaying Fort York, with a plan formally approved in 1833. Completed in 1841, New Fort York was situated 2,779 ft. west of Fort York and was initially only connected to a settlement via a pathway through Fort York. Although new fortifications were erected, the military continued to use Fort York’s batteries to help defend the harbor and the adjacent open space for drills and as a rifle range. In addition to its military uses, from 1839 to 1840, the old fort also hosted a Royal Society meteorological and magnetic observatory, before it was relocated to its permanent location at the University of King’s College campus. Plans were in place to also build three martello towers between Fort York and Gibraltar Point, although those plans were abandoned.